In the fictional world created by Terry Pratchett, the Discworld is held up by four giant elephants that in turn stand on top of the giant star turtle, as it travels through space. The fifth elephant is said to have crashed into the Discworld at the beginning of time, leaving a wealth of treasures. This may all seem very abstract, but I used to love reading the Discworld books of which there are forty one. They conjured up a magical world filled with wonder and awe, and in truth that is not too far from our world if we care to take the time to look about:

Coincidently this happened to be my fifth trip to our destination, but this time we had agreed that we would take in a few stops along the way there and back. After all orchid season is upon us and this offered a rare opportunity to look round somewhere quite different to all the local spots I frequent. Also with three of us heading out there would be more time to look about as we climbed, and as such I came home with a bounty of images. While I didn’t capture everything I saw there was enough to make me spilt this post into two halves:

This first half is about the trip in general, and the second half contains a good selection of the flowers, birds, reptiles, and insects. We didn’t need to have an early start and I left home on Friday at 7:30, picking up Rongy and then heading over to get Howsie. From there a three hour’ish north-north-easterly direction took us to Nonalling Nature Reserve. Here we had a bite to eat and popped the kettle on. The reserve, shown in the first image covers some 490 hectares and contains the lakes of White Water and Brown Lakes:

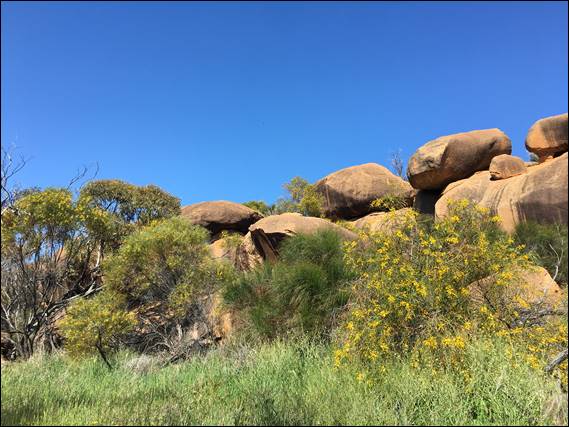

While we only scratched the surface of the first reserve, but what we saw didn’t strike us as being in particular good condition and we failed to find much of interest. But it was a lovely spot to stretch the legs, and once fed with a fresh cuppa ready for the next leg we drove to Totadgin Rock Nature Reserve. A sweltering 32 degrees, but we still walked the approx. 1km circuit that took us atop the granite outcrop. Here we found dragons scampering about and the gnamma holes, which still held water, providing thriving mini ecosystems:

Gnamma holes are natural depressions or rock-holes, which are formed by chemical weathering. These hold water for prolonged periods in areas where rainfall is low and sporadic, and were important sources of fresh water for Aboriginal people. The reserve was really worth spending time at. In addition to the dragons, we found quite a few orchids as we marvelled at other shrubs in bloom and of course the rock features. After an hour an half we hit the road again for the last leg that took us to Lake Campion Nature Reserve:

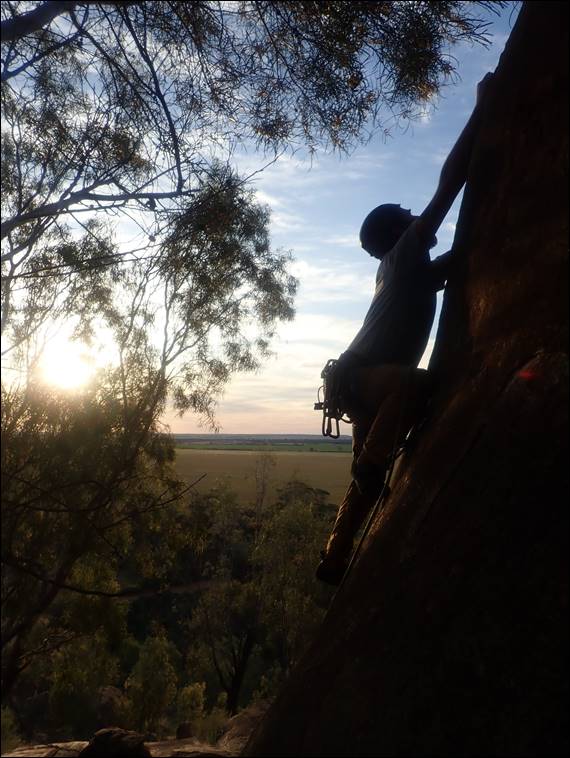

I have always considered this place to be called Lake Brown, but that is the name of the area to the north west. The, at times salt lake, that we have always stayed near is in fact called Lake Campion. On this trip, maybe a third of the lakes area looked to be underwater, and it is next to this lake that Eaglestone Rock sits. We arrived some seven hours after leaving Bunbury, giving us time to set up camp and head to the rock to get a few routes in. As I said, I have been here five times, and Rongy and Howsie have also been a few times:

We have probably climbed all the routes here that we are likely to, unless we had the inclination to train and go for the harder lines. At this point in time however, none of us had that inclination besides the climbing is different to anything else we have close by and there are enough routes to keep us interested for the few days. The last line was finished as the light faded, and we headed back to camp grateful for the meals that we, or in my case Lisa, had pre-prepared. Saving a lot of phaff time before we settled down, content after a great day:

Feeling a bit too early to hit the sack we decided to check the granite outcrop to see if we could find anything. With a bit of luck there would be a snake looking about for a feed, but as it was despite carefully lifting rocks and looking under ledges and boulders not a critter was about, other than spiders. We instead started to look at the gnamma holes, which had some aquatic bugs that magically come to life when water appears. As there is no connection with any permanent water bodies, there must be just enough soil for buried eggs to lie and wait:

Howsie spotted the above tiny leaf, being the fleshy leaf of an Elbow Orchid (Spiculaea ciliata) that is found in small pockets of shallow soil on granite outcrops. It is the only flower, bird, reptile, or insect image that made it into the first part of this post. That is because it is special find, being very different from all other orchids. The small leaf usually withers by the time the plant flowers in October to January, when the temperature can reach the high thirties. And despite the unbearable conditions I am pondering going back to see it in flower:

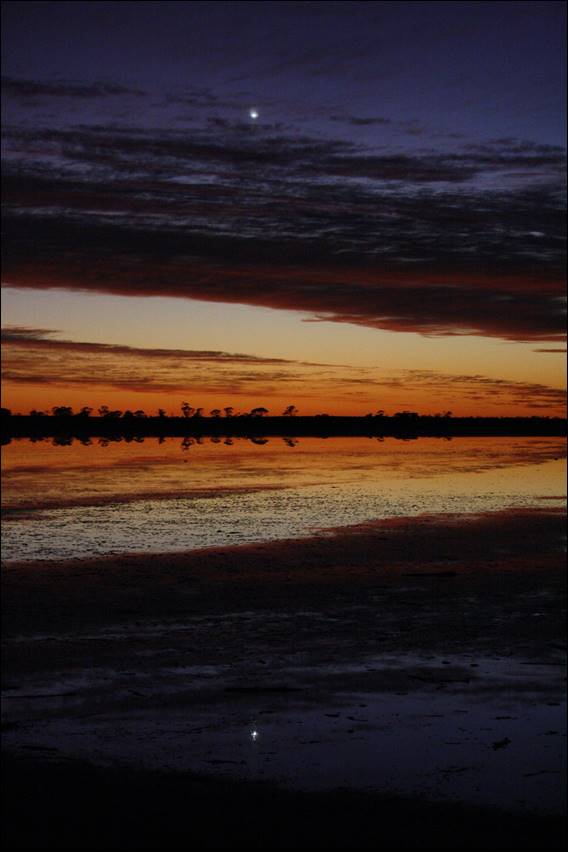

Back at camp we slid into our tents for the night. When camping I do enjoy watching the day wake up, and could be heard quietly pottering about to make a cuppa in the dark. Taking the welcome brew down to the edge of the lake to watch the sky fill with colours. Rongy joined me to watch a very spectacular sunrise, and it is possible that in order to capture the perfect moment I took just as many images of sunrises and sunsets as I did flowers, birds, reptiles, and insects. I have however culled them more heavily and also refrained from including too many:

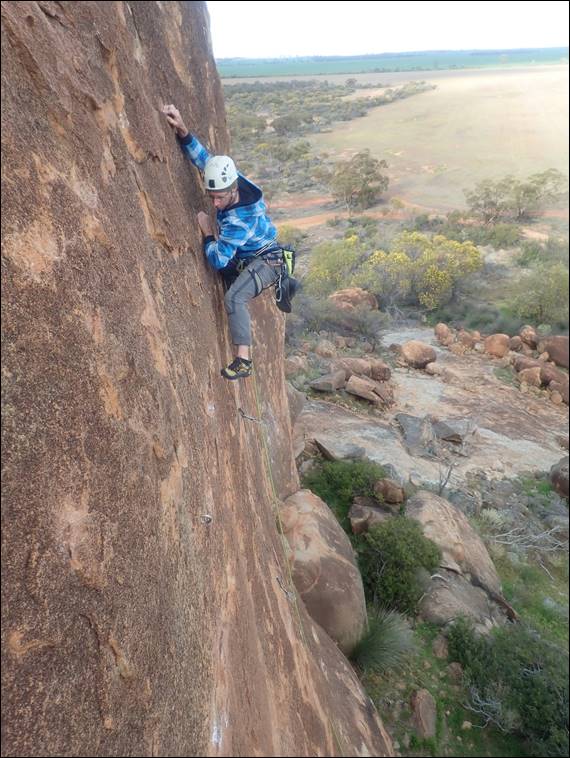

We knew it would be another hot day, so breakfast was soon cooked and eaten. Then a quick walk up to the rocks to crack on and get some routes under our belt before it got too hot. Something that has changed here is that the free camping has been limited to one area. We used to camp at the base of the rock, but that is no longer permitted. Mind you it really is not too far to walk, and controlling the camping here is probably not a bad thing. You may be able to make out the caravans nestled under the trees at the edge of the lake in the above image:

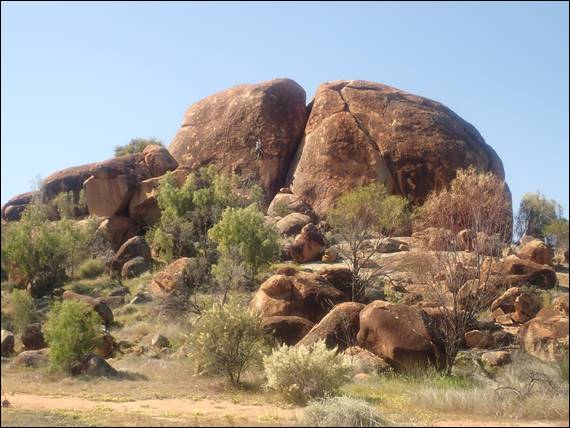

While there were quite a few staying at the campground, we were the only climbers and it was nice to have the place to ourselves. While it may be called Eaglestone Rock, I do feel that looking at the images again it could conceivably be an elephant with its body, head, and trunk laying down. And maybe this is where the fifth elephant was laid to rest, it certainly is a wonderful place. The landscape seems harsh and barren but we saw quite a few birds and insects, while the reptiles were a rare spot they were certainly about:

After packing in seven lines we were getting both hot and sore, so it was time to head back to camp for lunch and a cuppa. There seem to be a whisper of a breeze at camp and the shade was dappled at best, so it felt pretty stifling. Instead of enduring that, we went back to the rock where the shade it afforded, along with the breeze from being higher in the landscape made for a much cooler place. We got side-tracked and walked to the above isolated lake to check it out, but there wasn’t much to see so went back to rest in the shade of the fifth elephant:

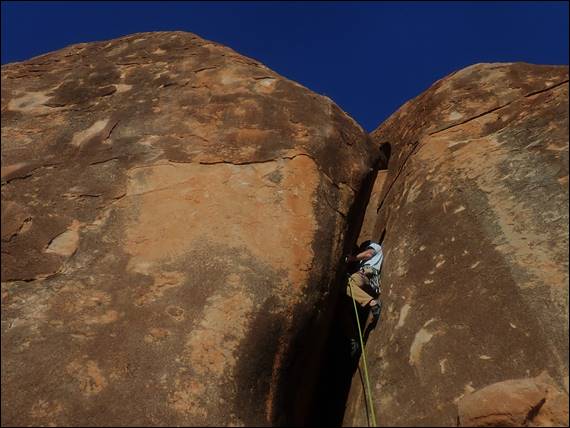

As things started to cool down we kicked things off again, Howsie had drawn the short straw and had to climb the chimney in full sun while Rongy and I snuck in shorter lines on the shady side. It was sweaty work and the rough granite was starting to wear down the skin on our fingers. The granite here is not as hard as that found at Welly Dam or round the Perth Hills, and you could see the texture starting to smooth off on quite a few holds. They were however still coarse enough to bite into the ever thinning layer of skin on our fingertips:

Three climbs in and we were ready to throw the towel in, plus none of the other routes were in any way inviting what with the still hot rock, sore bodies, and tender fingertips. The temperature finally started to dip as the sun lowered closer to the horizon, so we took a protracted route back to camp up and over the granite outcrops. The occasional dragon fled from our path, but not much else was to be seen. Another quick and easy reheat meal went down well, after which we ventured back to the isolated lake in the dark hoping to find frogs:

While we heard a few croaking they remained hidden, and we ambled back to lie down for the night. I was up earlier than the first morning and discovered a setting on my camera that I hadn’t played with before. So set it up and left it for half an hour to track the stars as the light once more crept into the sky. The camera did its thing, and I got the kettle on for the first brew of the morning. This time all three of us took a brew down and watched the light show at the edge of Champion Lake. As we broke camp no one was prepared to commit as to whether to squeeze a climb in:

So I made an executive decision. We packed the car and drove to the base of the rock, agreeing to one route each. Repeating lines form the previous day, but they are very good and each of us led a line we had not led the day before. One each was sufficient, the fingertips didn’t feel like they had recovered enough and the bodies seemed happy not to have to endure anymore. Besides we had the long journey home today, during which we aimed to stop in at one more nature reserve requiring a reasonable detour. Heading off we let the fifth elephant rest in peace:

On the way to Kokerbin Nature Reserve we saw several big outcrops that yearned for us to stop and hike up to them, but I kept driving and all was forgiven when we saw the third largest monolith in Australia. Coming in after Mount Wudinna in South Australia and of course Uluru in the Northern Territory, as the largest. This claim is hotly contended, as is the second spot, so it may or may not be the third largest. Regardless, interesting natural architecture and boulders strewn round the base with shrubs in flower made for a magnificent sight:

We walked up the 122m it rises above the surrounds, watching out for movement and orchids. Taking in the view once on top, while enjoying the aerial combat of butterflies aggressively protecting their patch. We didn’t stay as long as the reserve deserved, but it was pretty hot again and we still had four hours in the car ahead of us. I did however, after being impressed with a couple of the reserves we had visited, make a mental note to suggest to Lisa we consider a Wheatbelt road trip sometime to check out a few more reserves:

The next section is for the nature enthusiast to read, or if you just want a stickybeak you can flick through the images of just some of the treasures we spotted in this small but magical slice of the world. And while I have the chance I’ll pop in another sunrise image:

I’m pretty sure that we spotted both the Little Laughing Leek Orchid (Prasophyllum gracile) and Laughing Leek Orchid (Prasophyllum macrostachyum), with this being the Laughing Leek Orchid based on the darker flowers. These leek orchids don’t grow very tall and are found all over, but in drier places are limited to areas where water pools, such as the gnamma holes on granite outcrops. These were only noticed at the Totadgin Rock Nature Reserve:

While a common orchid in Western Australia, South Australia, and Victoria this next species is considered endangered in Tasmania due to the isolated and small areas it can be found. Despite generally being common, I do not recall seeing the Lemon-Scented Sun Orchid (Thelymitra antennifera) before but I could be wrong. On this trip we found this cheerful looking orchid at both the Totadgin Rock & Kokerbin Nature Reserve:

The Yellow Granite Donkey Orchid (Diuris hazeliae) was found in numbers both in the wet gnamma holes of Totadgin Rock Nature Reserve & Eaglestone Rock, and also along the base of the former granite dome in the surrounding wet soils. I’m confident in identifying this one based on the descriptions I’ve found, being a species that it is almost exclusively found on granite outcrops:

Another first time find for me is this Mallee Banded Greenhood (Pterostylis arbuscula). I’ve based this on the plant height, and singular nature and colour of the flower, which was sadly on its way out. This aligns with its flowering period of June to early September, and we found a second specimen with two flowers that was even further gone. It is also a bit of a giveaway that we found it in amongst Mallee shrubland at the Totadgin Rock Nature Reserve:

While I have seen plenty of Blue Fairy Orchids (Pheladenia deformis) I have generally only observed the pale blue variety, so this more purple tinged specimen at Totadgin Rock Nature Reserve was a great find. Again close to the end of its flowering period, so the flower was a little wilted. It is the only species of the Pheladenia genus that is endemic to Australia, being found all over the country other than in Queensland and the Northern Territory:

The final orchid find was a small scattering of dainty Sugar Orchids (Ericksonella saccharata) at the Kokerbin Nature Reserve. This orchid was previously included with the Caladenia genus, which includes the Sugar Candy Orchid that I have seen before. But has since been given its own genus with this being the only species. It is smaller than the Sugar Candy Orchid and found throughout the Wheatbelt, whereas the Sugar Candy Orchid does not extend as far inland, preferring moist and swampy locations:

Of all the birds I spotted this was by far my favourite, despite being the most common of the four pardalote species and the least colourful. As I watched the climbing action or inaction on Emu Walking at Eaglestone Rock, sorry Rongy and Howsie, this Striated Pardalote (Pardalotus striatus) landed within meters of me and sang its heart out. After several minutes it flew off, but it returned again during the morning and that time it seemed content to just sit near me with no song:

As we climbed at Eaglestone Rock it only seemed appropriate to have a Wedge-Tailed Eagle (Aquila audax) soaring high above us, with the unmistakable shape of its tail. We also spotted one sat in a tree as we approached the Kokerbin Nature Reserve but didn’t stop and try and take an image. Generally they are happy to sit and watch you drive past, but as soon as you stop they will often fly off, so we let is rest:

The Australian Ringneck Parrot may seem like an unlikely one to include here, but as we watched this one at Eaglestone Rock the different pattern of this sub-species was pointed out to me. There are four subspecies, and this one is the one Lisa and I used to see so often in Alice Springs, being the Port Lincoln Parrot (Barnardius zonarius zonarius) and distinguished by the yellow belly. In the South West of Western Australia we generally see the Twenty-eight Parrot (Barnardius zonarius semitorquatus), which does not have the yellow belly:

Another familiar and commonly seen bird of prey that watched, as we climbed on Eaglestone Rock, was the Nankeen Kestrel (Falco cenchroides). So common in fact we saw it pretty well everywhere we went and also as we drove. Often hovering in one spot looking down for prey, and as the name suggest it is from the Falco Genus, or Falcons. Found both here in Australia and New Guinea, and being one of the smallest Falcon species:

Walking back to the car at the Kokerbin Nature Reserve this Singing Honeyeater (Gavicalis virescens) landed just of the path and seemed to want me to taken an image. At first I just watched it, but it stayed close and after I eventually reached for my camera and took a few shots it only stayed for a moment longer. With some 55 genera and 186 species of honeyeaters, the Singing Honeyeater is found across the widest range covering most of Australia:

There were of course many, many Bobtails (Tiliqua rugose) mostly on the road as we drove along, with a few as roadkill due to unobservant or uninterested drivers. I sent a picture of one of the two we spotted in the Totadgin Rock and Kokerbin Nature Reserves to Chris, my uncle in Holland, and the name Bobtail had him perplexed. So he researched it and sent me some details about them including another of their common names the Blue-Tongued Skink, and this images clearly shows where that comes from:

We saw many Ornate Crevice Dragons (Ctenophorus ornatus) at both the Totadgin Rock and Kokerbin Nature Reserve. We had to keep a sharp eye out as they are very well camouflaged, and it only when they move that you spot them. Often they started to bob their head before they ran to a narrow crevice to hide in. They inhabit granite outcrops, rarely leaving these landforms other than to give birth. Due to all the clearing newborns do not move between outcrops as much anymore resulting in a reduction in genetic diversity, which increases the risk of eventual extinction:

When we got to the Nonalling Nature Reserve it was not looking all that promising, but due to the lake there was a hive of activity in and about the fringing vegetation. Sitting there for a while I manage to snap pictures of three different damselflies. Dragonflies hold their wings out to the side, and damselflies hold theirs along their bodies when resting. Damselflies are also generally slimier and both wings are of the same size. This means that unlike dragonflies, which have smaller back wings, they can’t fly backwards:

You’ll notice I have skirted round saying what damselfly is in the above image, which is because I have really struggled to work it out. I was also intrigued by the way the abdomen is at ninety degrees to the prothorax, which I have not noticed while trawling hundreds of images while trying to identify it. All the online images show the body straight, like the two below that I think are a male and female Western Ringtail (Austrolestes aleison):

This species is endemic to South West Australia, extending as far north as we were heading on our trip. The male is blue and black, above, and the female is a duller colour, but with similar patterning. If I really wanted to be sure of this identification I would need to check the top of the second segment of the abdomen, which has a goblet-shaped pattern. This is where the species name aleison is from, derived from a Greek word meaning a goblet:

On arrival at the campsite at Eaglestone Rock this Velvet Ant (Bothriomutilla rugicollis) was spotted in the scrub. It is in fact not an ant at all, being a wingless female wasp. Only the males have wings, and like any wasp they can deliver a painful sting. They are parasitoid, meaning its young develop on or within another organism. They lay their eggs near the eggs or larva of a host, and when the velvet ant larvae hatches a meal is ready and waiting:

With all the blossoms out and having time to sit about and look round at Eaglestone Rock there were lots of insects about, this one really caught my eye. A female Gasteruptiid Wasp (Gasteruption sp), another parasitoid. I’ve not managed to narrow it down to a species of which there are many. This one lays its eggs inside the another wasp and solitary bee, which are bees that live alone but at times nest close together. Only the female has the distinctive white-tipped ovipositor, and as you may guess that is used drill into the host to inject eggs:

As we walked up the granite dome of Kokerbin Nature Reserve if you kept a sharp eye out you’d see movement on the rock near your feet. In all cases I spotted movement it was a Red Tiger Assassin Bug (Havinthus rufovarius). While small if threatened they might bite. They use venom to paralyse and liquefy prey, and it can also be very painful for people. They watched as I approached and backed off always facing me down, as opposed to turning and running:

Finally, there are six common mosquito species in Western Australia. This one is likely to be Aedes vigilax, based on where it hitched a ride and that it was extremely active in the day. This species has by far the highest ability to travel from its breading site, at up to 100km. It became engorged with blood from one of us, along with two others that entered the car at the Kokerbin Nature Reserve, before the final four hour stretch of the homeward journey. I might even dig out The Fifth Elephant and read it again: