Someone had hinted the week leading up to Christmas would provide the kind of conditions that would result in great scuba diving conditions, which I felt indicated the nearshore snorkelling conditions may also be much improved. Full of anticipation, I took the plunge on Friday morning and was a little disappointed with the visibility. It also seemed that the life we would normally expect in the warming waters of summer had not kicked into action. This resulted in me needing to scour the reef that extra bit harder to find anything that seemed unusual or worthy of a look-see:

Above an Old Wife (Enoplosus armatus) was watching me carefully, and was one of the few fish I went down to check out. The name might seem politically incorrect, in these days, and the rationale for it would only go to strengthen how some people would feel about that. When hooked and brought up these fish are said to grind their teeth together making the sound like an ‘old wife’, whatever that aims to infer. Whereas, the Latin name is more apt, with armatus meaning armed with sharp spines, relating to the fish’s dorsal spine that is venomous:

I did a lot of checking under ledges, in hope of something fun but all seemed quiet. The above did however catch my eye, I have seen these dark looking ‘things’ in the crevices of rocks but can’t recall ever seeing one attached to seaweed. Much to my surprise it is a Feather Star of the class Crinoidea, and I have not attempted to narrow it down any more. Referred to as Crinoids, when young these marine animals can have stalks to keep them securely in place. As they mature those that keep the stalk are known as Sea Lilies while those that loose it are known as Feather Stars:

It was hard to sit and watch the Feather Star, and in the image below you can almost feel the movement in the water. I got a great view of this Western Rock Octopus (Octopus djinda), shown above and below. By day they are usually hidden away, watching the world from their protective lair or camouflaged by a collection of rocks, shells and other matter they use to cover their soft bodies. This one was using neither, being in the open and that allowed me to get glimpses of all the tentacles. But the movement of the water made it impossible to get a good image, as the weed swished this way and that:

My persistence paid off again when I stumbled across a couple of adult Red-netted Nudibranchs (Goniobranchus tinctorius). They were much bigger than the young I had seen just five days before. They mature quite quickly, and these creatures never live longer than a year, in the wild, and some species less than a month. It is also sad that these very attractive and brilliantly coloured animals have very poor eyesight, so are unable to observe their own beauty. Unlike other creatures their spectacular appearance is not used to attract a mate, but to ward off predators:

As I was preparing to get out I spotted a good sized adult Brownspotted Wrasse (Notolabrus parilus) having a go at a sea urchin, which had found itself in an open sandy patch. Watching from a distance I saw the large fish circling the urchin, and going in to seemingly nip at the protective spins. Despite what looks like a defence system that is impossible to breach, the Brownspotted Wrasse is known to feed on sea urchins. So I am glad I didn’t disturb it by going down for a closer inspection, and headed to shore. Christmas morning arrived and with it the promise of an increasing swell:

There were therefore three reasons for an early snorkel, wanting to catch the low tide, avoid the increasing swell, and to not be about when the throngs of people, which would no doubt invade the beach, arrived. I was a little worried when I walked down and saw the above jet ski bobbing about on the water. Personally I think they are one of the most useless boy toys you can get. Being no use, off a beach, for anything but honing about. Fortunately, they left soon after I entered in the water so there was no risk of being run over by it. And allowing me to focus on what lay beneath, rather than worrying about what could have been above:

The visibility had gotten worse, this was in part due to the low sun but there was also a lot more weed floating about in the water, indicating the swells had been up. So as before I spent a lot of time looking extra hard, when out of the corner of my eye one and then a second large Samson Fish (Seriola hippos) came close by. I mentioned before how these fish display non-feeding behaviour during spawning, the reason being that their empty stomach creates more room to allow for larger ovaries. This in turn enables them to maximise how many eggs they can produce:

After a couple of circuits round me the large fish were lost in the soup, and I refocused on the sea floor. Here I spotted a long antenna poking out, and was happy when I was able to get fairly close to take this image. It could have been one of two species, being the Western Rock Lobster (Panulirus cygnus) or Southern Rock Lobster (Jasus edwardsii), the first is identified by a single white dot on the outside edge of each tail segment and the second by a single spine between the eyes. At the time I was unable to tell which it was, but with the reasonably clear image can confirm it was the smaller Western Rock Lobster species:

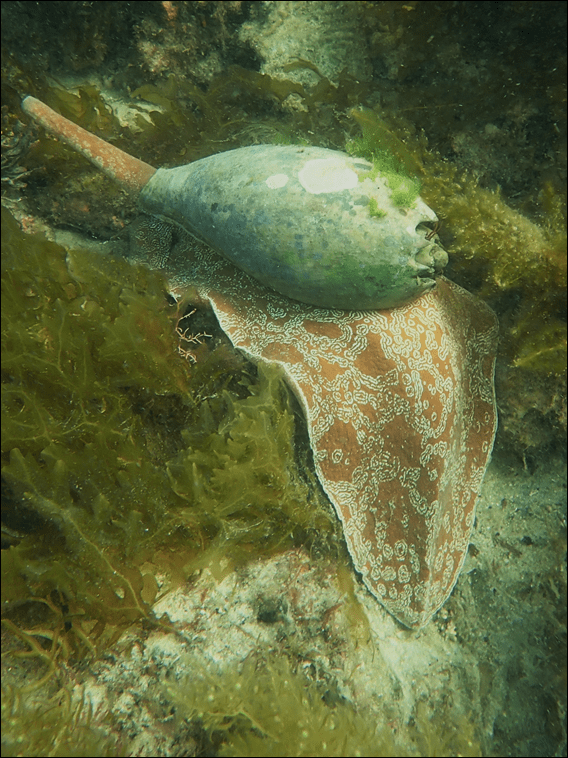

The swell was already picking up and the force of the water pushed this Southern Baler shell (Melo miltonis) out from under a ledge. To give you an indication of scale the shell on this one was approx. a foot long. I watched it tumble down and get rolled about by the water, until finally it stabilised itself and managed to get upright. Then it slowly made its way back into its daytime hiding place. I have dug a little deeper about their feeding habits and now know, these gentle looking gastropods, suffocate their prey with their large foot. I am still however none the wiser as to how they get their prey out of the shells, so will need to keep digging: