During a clear out Dave James had a mob of old guidebooks on offer and I was lucky enough to get some 1970 guidebooks for a range of places I have climbed in the UK, including the Peak District, Lakes District and North Wales. The thing about those older guidebooks, and dare I say the format of guidebooks in the UK, is that they are a great read. Unlike many quick access, minimal detail guidebooks of today these are packed with information that could make an armchair climber out of me. The reason for this email is because I started to muse upon some of the aspects that these 40-50 year old tomes were touching on.

Access

Back in the day many climbing areas were located on private property. Indeed even the status of being in a National Park did not secure access, as the land within these areas was not being secured by the crown. That would not happen until later. As such it all came down to good relationships and of course how to manage competing interests. For the Peak District the main conflicts came about due to limestone quarrying and conservation reasons. The guidebooks made no mention of the contrasting nature of these two interests in their own right. I’m guessing that the greater economic gains in quarrying may well have outweighed any conservation values back then. Then there was also the conflict with the grouse shooting enthusiasts, a much more gentrified, respected and supported activity of the time, and as the image below shows fun for all the family:

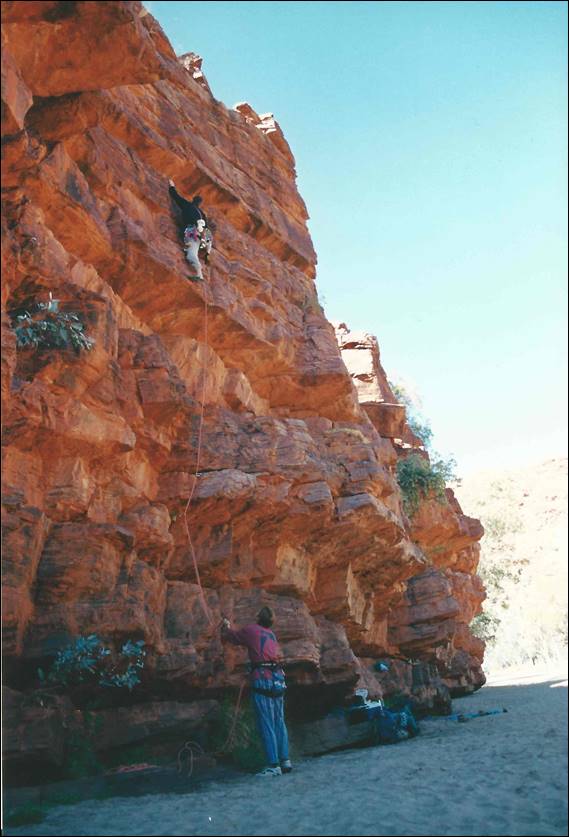

Hikers and climbers were attracted to certain locations, and this made businesses more profitable in those areas. Pubs and hotels were becoming more common in spots known to attract the outdoor enthusiast (as well as the “general” tourists), which only helped boost the popularity of these locations. It also meant that the more remote locations with no facilities received less visitors, and at times also slipped into obscurity. As the legislation for National Parks changed, more land was purchased for management by the crown and this provided an opportunity for more secure access to climbing areas. The change in legislation and the opportunity it brought required the climbing community to rally together to put a good position together to influence the management plans for these areas. One of the guidebooks stated that whatever you may think of the BMC (British Mountaineering Committee) in relation to access for climbing they are on your side, so support them. Over time the view of the priority for areas shifts, and we still lose access to areas even within National Parks such as Trephina Gorge in Alice Springs:

The environment

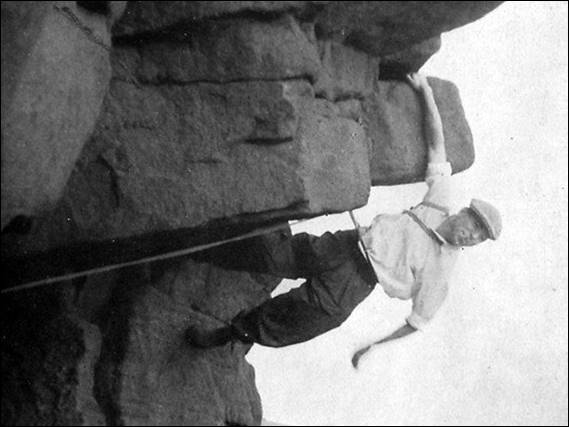

Back then just like now access is ultimately at the mercy of good relationships and the responsible behaviour of climbers. While I have often heard it said that people who undertake outdoor pursuits have a greater respect for the environment, these old guidebooks talk about issues that are commonly frowned upon now. Fires and damage to property were key issues that were cited but more surprisingly litter was also mentioned. This included specific mention of “discarded fag packets, broken bottles and discarded socks”. The broken glass did surprise me. While it is something that I certainly associate with Australia, I never came across broken glass in the UK or other countries I’ve climbed. I was not however surprised to hear about socks, which were placed over the shoes on wet days to soak up the moisture. Also fags packets wasn’t a big surprise, as this old image of Joe Brown shows climbing while smoking was not uncommon:

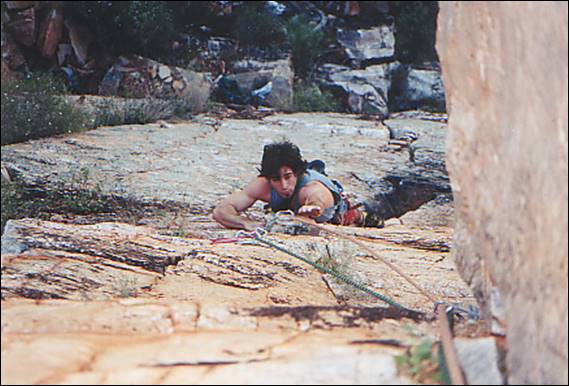

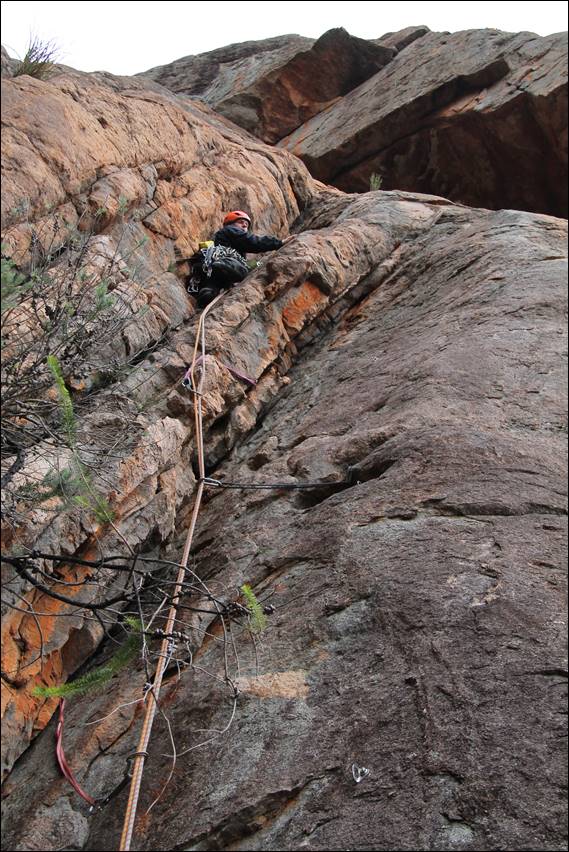

Then there is the matter of the issue of “over cleaning of routes is striping once life filled crags into bare rock deserts”. Particular attention was paid to this in the guidebooks of North Wales and the area that offers the unique environment required for the rare Snowdonian Lilly, which was only found specific crags. Originally these plants receded to mountain areas as the climate started to change (yes these old guidebooks mention climate change!). They then receded further to three specific crags that offered sanctuary from grazing animals as well as being hard for the avid botanist/collector to get to. These plants favour more basic soils high in lime, which with agricultural practises on the slopes changing the soils could then only be found on the ledges and in the cracks of these crags. Originally vegetated lines were not looked at by past climbers, but as options for new routes reduced these vegetated areas were being explored. I found reference in two guides that requested the activity of “gardening” being minimised and if at all possible avoided. Today over enthusiastic cleaning of lines still occurs, and I too have been guilty of cleaning lines while attempting an FA such as the aptly named Where’s the Gardener in the East McDonalds of central Australia:

Indoor walls

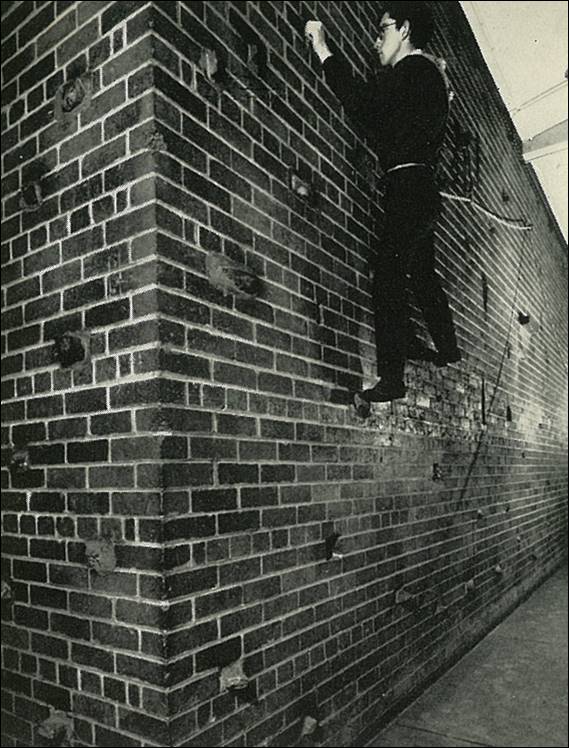

Ok I admit that these guidebooks did not mention the practise of indoor climbing, but to make this ditty flow it is an important consideration. In 1960 Ullswater School in Penrith in the Lake District had a purpose built climbing wall made. One wall of the school’s new gym used bricks and stone to create hand and foot holds, it even had a metal bar along the top to allow top-roping. The first known finger-board or campus-board came into effect shortly afterwards in 1961, when wooden slats were glued to the wall of the sports hall of Royal Wolverhampton School in West Midlands. These were used to build finger strength and maintain stamina in the off-season. Then came the iconic wall at the Leeds University in 1964. Commonly thought to be the first wall, this one used glued-on rocks and stones on an existing brick wall to simulate movements that climbers would make outside. So why is all this important, well it shows a distinct shift in the approach to climbing. Previously a pastime of the real adventurer, this marked a change to more of a sport mentality:

Why and how we climb

Having learnt to climb in the UK, where traditional climbing far outweighs sport climbing, I have a passion for ground-up ascents. Although admittedly that has changed a bit since being in Australia, for a variety of reasons. All of the guidebooks I read focused on the same changes that were starting to occur. These included the “rigging of routes, resting in the harness, pre-placing protection and/or placing pegs”, they go on to say these practices are frowned upon and “reduce the standard of the route”‘. Interestingly they do not say that the difficulty of the route is reduced but hint that the ideology of climbing is being threatened. Also with indoor climbing starting to take hold the use of gymnastics chalk was occurring and this was viewed as “another objectionable trend” that “results in the crag looking like a zebra”. Ultimately in these guidebooks the editors were still pushing the previous era’s ethics of ground up ascents:

However, things were changing and that could not be ignored. So with a growing focus of climbers on building stamina and strength, more demanding routes were being established, at times with less and harder to place protection. The guidebooks recognised that there was more emphasis being place on steepness of routes, to increase difficulty, even if the routes no longer lead anywhere. There are arguments put forward that the old routes had merits such as “fine positions” and “at least led the party to the top of the crag”. Tremadog in North Wales had very steep walls and lent itself to the practice of pre-placing gear, abseiling in, top roping, placing pegs and also the practice of what was called yo-yo. This was described as “to be lowered from a difficult section and then re-climbing back up to that point” and was equally frowned upon. It was also noted that with steeper climbs being developed elsewhere the “old style of balance” required for slabs had “fallen into disuse by many”. Even today slab climbing is a style many are not comfortable with. This resulted in “a call to upgrade some areas that have led some people into false illusions and created fatal outcomes”, notable Idwall Slabs in North Wales:

There was however resistance to changing grades on such a scale, and the debate as to the changing expectations of the modern climber came into play. Slab climbing in particular was noted as “maybe not offering such high grades (but) often beat back the parties with high aspirations, after success in other areas, in part due to the more spaced protection and less holds”. All the aspects of slab climbing that makes it what it is! Climbs and/or areas that were “being left idle” were omitted from the guidebooks, on the basis that the “climbing public is served better by a guide book that is not cluttered by descriptions of routes which are unlikely to be repeated”. What was not detailed is whether these climbs/areas were not frequented due to changing practices and expectations or indeed ease of access or close by facilities. It is also worth noting the guidebooks identified better quality routes using stars, which were given based on other routes in the entire area and general consensus. Today starred routes are often used to identify the best lines in a local area or on a single crag, and new routes are awarded stars before anyone else has climbed them. Finally, the guidebooks mention that some areas received very little light and as such the holds often “have a little grease and moss” which is said to “add to the fun”. These areas were not frequented by the modern, more sport orientated, climber left instead only to the adventure climber. Some of us still go out and enjoy these less predictable and “perfect” conditions:

Protection

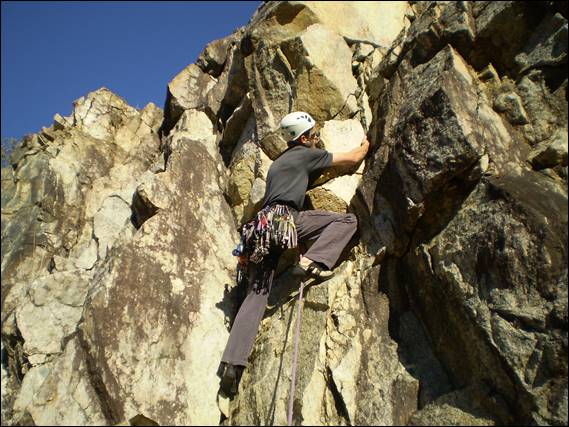

I mentioned above the practice of cleaning routes. There was very little discussion about the old day tools that were used, such as hobnailed boots, that certainly left their mark on the rock faces. Scarring them and often resulting in more rock being dislodged than if a normal walking boot had been used. I mention this as the wire brush was a tool that was being introduced, it came alongside the use of chalk and the changing practice of focusing on harder lines and needing to make sure they were both safe and in condition. There were some who had nothing less than loathing for the new climber, who came along and vigorously cleaned routes before attempting them. Pete Livesey raised the bar during the 1970s, and is reputed to be one of the finest climbers the UK has ever produced. He was known for his professional (indoor) training regime and was accused (but not proven) of not only wire brushing but also chipping the rock to create edges to make the line of Downhill Racer at Froggatt Edge in the Peak District achievable:

The guidebooks make many references to the introduction of pegs, used of course for decades in alpine climbing but now starting to be used on the crags in the UK. This was evident as far back as 1936 when the Munich School visited North Wales and found nothing hard enough, so created they own route using three pitons on their 230ft route called The Munich Climb. The guide said that these pitons “had to the removed”. The guidebook goes on to accept things are changing but the author made it clear that the use of pegs and wedges was considered to be “out of place for the area”. Indeed some of the classic hard-man routes of North Wales used all of the techniques frowned upon including the use of pegs. Ron Fawcett was one of the first climbers to receive sponsorship, recognition of his unfathomable talent. When this Yorkshire boy visited North Wales in the 1970s and established Lord of the Flies (still a test piece today), it was the ethics of prior inspection and use of a pre-placed peg, not his achievement, that was discussed by the locals:

Stronger words were used when research for the guidebook found that “some valley classic climbs had been defaced by pitons”. On one route a climber was witnessed placing sixteen pitons on a classic climb established in 1919 and led countless times since without them. The guidebooks suggested that the attitude was shifting and people who had technical ability, but not the mental ability were guilty of placing additional protection where it was not previously used. They went on to state that “clearly we have reach a point of crisis” and while “our pitonless ethic is the envy of climbers throughout the world, all of whom are striving to get their crude beginnings and get their cliffs into a piton-free state” it was also conceded that this situation was something too difficult to unravel in a guidebook. That said one guidebook stated “the instincts of a the climber to do his own thing and reject those who tell him to conform to a group pattern”. As such who is to say the ethics of the former years should be adhered to as we move forward. So should the new ethics result in former classics being “defaced” as a result of the modern ethics? One of many examples I’ve come across being the classic fully trad line of Juluka at Peak Charles in Western Australia, which someone in recent years decided to bolt:

Looking forwards

The discussion of access and ethical purity will continue to change and challenge the climbing community. Today climbing is viewed as a national sport in some countries, but in other places it is considered a reckless and pointless activity. So the strong words each guidebook used on the need to do the right thing to continue to secure access is still very relevant. While the guidebooks suggested that some of the areas have been “climbed out”, they also acknowledged that with changing ethics no doubt more routes will continue to be established.

One thought on “Timeless issues”